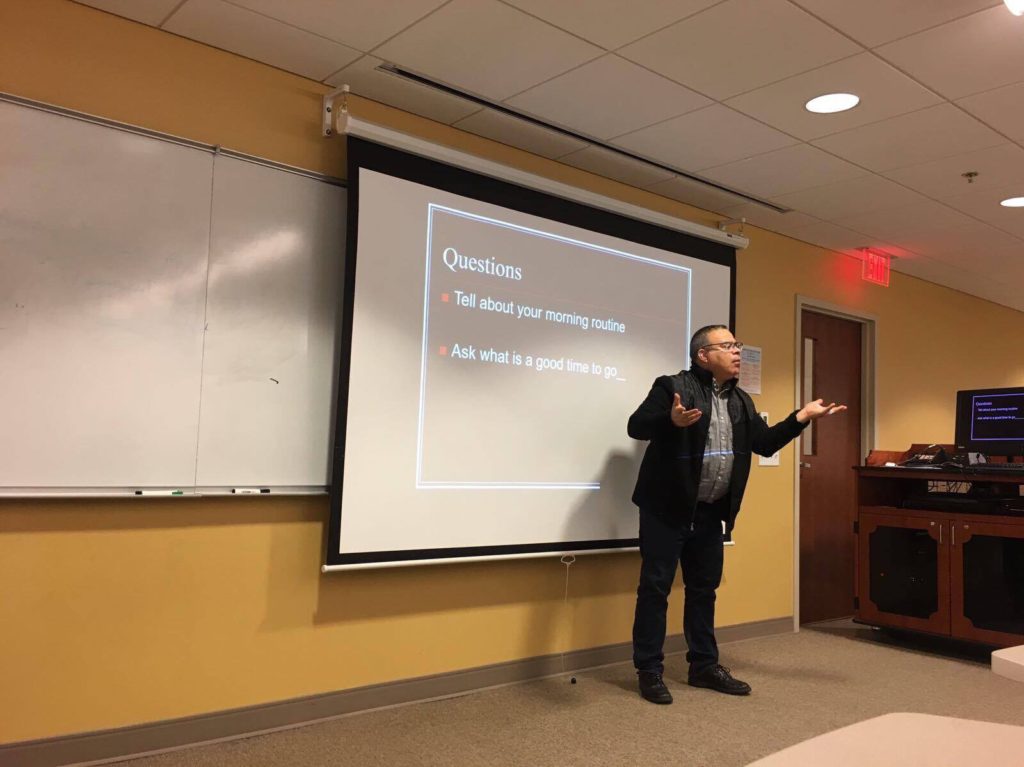

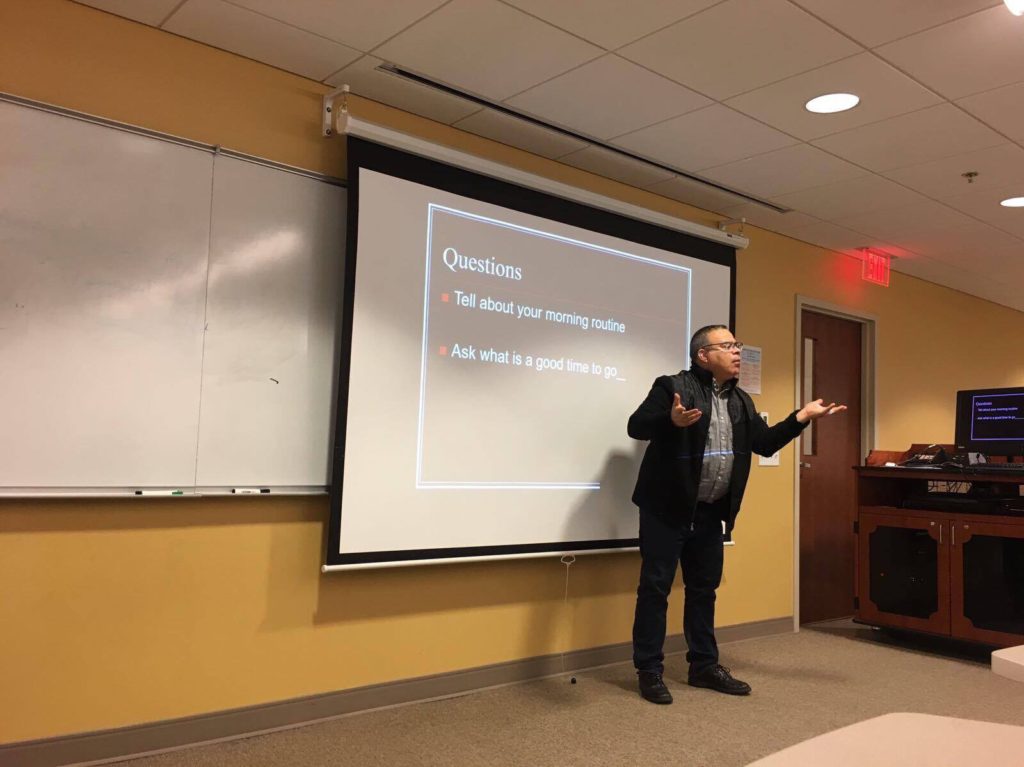

Professor Mario Hernandez Inspires an Interest in American Sign Language

Professor Hernandez teaching one of his sign language courses. Courtesy of Fabian Huber

By Contributor Fabian Huber

With his thumb and index finger shaped like a “C”, Professor Mario Hernandez slowly leads his right hand to his upper body and taps it twice on his chest. “Police,” he stammers, barely audible, stressing every syllable of the word by moving his lips like an opera singer. Fourteen students watch each of Hernandez’s moves before they imitate him. A faint tapping sound fills the classroom. The professor puts on a bright smile, lets out a joyful “Yes!”, and claps his hands.

Hernandez, a 51-year-old Brooklyn native, is one of approximately 500,000 Americans to speak American Sign Language (ASL). And, thanks to him, this number could rise, if only a little. A part-time lecturer for ASL at the Catholic University of America, Hernandez teaches the only class within the University’s Department of Modern Languages and Literatures that operates with almost no spoken word.

About three out of every one thousand children in the United States are born with a certain degree of hearing loss, mostly to hearing parents, according to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Sign language closes a social gap by enabling deaf individuals to either communicate with each other or with their sign language-speaking family, friends, or colleagues. It is a language in and of itself, very distinct from English, consisting of hand, face, or torso movements and facial expressions.

“ASL is a very living language. It develops just like a spoken language. But instead of normal babbling we start with physical babbling,” said Hernandez, who was born deaf and communicated his answers to questions for this piece in writing.

Over the years, Hernandez has perfected his lipreading, so if his students struggle using sign language, he is able to understand them if they speak slowly. Students are graded on midterm and final video exams, dialogues with Hernandez, a term paper, and weekly video assignments. In some of these weekly assignments, students are challenged to spell their names or form easy sentences and then upload them to a website.

Hernandez’s class is an interactive dialogue between participating students and a passionate teacher. In a class about different professions, for instance, Hernandez first showed the signs and told his students to copy him. Then, he asked them for the rationale of each sign. When signing “police”, the “C” stands for “cop” and the tap to the chest represents the badge. After Hernandez had made sure that every single student understood, he gave them a thumbs up and a laugh.

Isabelle Canals is a freshman currently taking Hernandez’s sign language class at Catholic.

“I like to call him an actor-type of personality. He gives it all every class. Even though the classes are the same, he finds a way to make it different for each individual,” Canals said.

Unlike many of Canals’ classmates who study nursing, the psychological and brain sciences major decided to take the ASL course out of interest rather than as part of her studies.

“I feel like language is a huge barrier in the modern day world,” she said. “So if I can just learn one more language, then that’s one more person I can communicate with.”

Canals took a Spanish Sign Language course in sixth grade back at home in San Juan, Puerto Rico. She practiced by herself but soon figured out that she prefered an actual teacher talking to her. With Hernandez, Canals found someone able to improve her sign language skills.

“He’s an amazing professor. He meets you halfway. If you have trouble spelling something or just saying something, he has no problem slowing down,” Canals said.

The fact that Hernandez wants to be understanding and meet his students on the same level is also reflected in his course syllabus. Under a section titled “Advice” Hernandez says: “Do not fear learning to speak American Sign Language. Welcome aboard, my friend!” The general rule of the classroom: “I don’t bite you, never!”

Suzanna Kwoka, 24, from Glastonbury, Connecticut, feared neither learning ASL nor getting bitten by her former teacher. Now working as Director of Communications for a New England-based computer firm, the Catholic alumna took Hernandez’s introductory class in the spring of 2014 and was so hooked that she decided to continue studying ASL. As Catholic does not offer follow-up sign language classes in fall terms, she took an advanced class at Gallaudet University, a D.C. college focused on the education of the deaf and hard of hearing.

Thinking back, Kwoka has nothing but good memories of Hernandez.

“He is not just teaching something that he’s very knowledgeable about. He is teaching us his way of life, his culture,” Kwoka said. “It was very fun and it was a whole lot of learning centered around your peers.”

Hernandez, who said that he was mainly hired by Catholic in 2004 to teach nursing major students, is also a highly-regarded colleague within his department.

“Mr. Hernandez is an excellent instructor and a wonderful mentor to our ASL students,” said Claudia Bornholdt, chair of the Department of Modern Languages and Literatures.

According to Bornholdt, there are thirty-nine currently-enrolled students in his two introductory sign language classes.

Hernandez sprinkles a little side note from his everyday experience into every lecture to make his students understand what it actually means to master life as a deaf person.

Canals recalled a moment in which her sign language knowledge led to a potential friendship.

The other day, she was invited to a Diwali party, celebrating the Indian new year. She saw a group of three people communicating in sign language. As the group was about to leave, she gave it a shot. Canals tapped them and said “Hi!” in sign language. All of a sudden – even though Canals had just taken ASL for a couple of weeks – the language barriers, the social gaps, all of the other obstacles that interfere in relationships between deaf and hearing people, were gone.

“It is likely that they eventually forget ASL,” Hernandez said when being asked about his students. “But I want to raise awareness and sensitivity. And I try my best.”