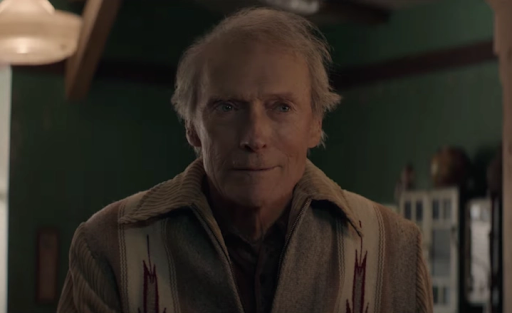

Cry Macho: A Tragic Disaster

Image Courtesy of Warner Bros.

By Dean Robbins

Clint Eastwood was ninety years old when he starred in Cry Macho. That alone is quite the achievement. Cry Macho is clearly intended as a swan song for the type of masculinity Eastwood once personified. The problem is that it is barely a swan song. If it is anything, it is a relic of a relic; an echo.

Cry Macho, also directed by Eastwood, is a soft and small tale about an old horse breeder (Eastwood) in Mexico trying to find the thirteen-year-old son Rafo (Eduardo Minett) of his former boss (Dwight Yoakam). Within the first ten minutes of Cry Macho, Eastwood’s Mike Milo is fired from his job and then quickly recruited to kidnap a boy in Mexico by the same boss who fired him. The whole sequence is completely botched from rushed pacing to the first in a series of horrible performances, this time by Dwight Yoakam. Before one can say “high plains drifter,” Milo is in Mexico getting seduced by Rafo’s seductive mother Leta (Fernanda Urrejola).

The first act gives the viewer a bit of whiplash until it settles down. Mike is in Mexico with Rafo and they live a surprisingly peaceful life for most of the movie. Unfortunately, it settles down to the point where it is barely even functioning. The film begins and quickly finds itself in a vegetative state until the credits roll. The central relationship between Milo and Rafo, for instance, never gets off the ground and barely stays on the runway.

The film’s real heart may be in a romance between Milo and bar owner Marta (Natalia Traven). The writers Nick Schenk and N. Richard Nash, the latter of whom died over twenty years ago, certainly think this is the emotional core, considering how they choose to conclude the film. However, Cry Macho never really explores this relationship beyond Marta thinking Mike is a decent guy. The story, in general, is a major misfire from beginning to end. There is a dearth of tension shown in the way many potentially intense scenes disengage quickly.

Overall, the film is sleepy, even on a technical level. Cinematographer Ben Davis, who has turned in good work on films like Guardians of the Galaxy (2014) and Three Billboards Over Ebbing, Missouri (2017), creates something unmemorable here. Pastoral Mexican settings are rendered nearly colorless and shot construction rarely does anything further than what is necessary for establishing the basics of what is happening. The editing by regular Eastwood collaborators David S. Cox and Joel Cox is often jarring, with poor transitions that are worsened by the bad script.

Cry Macho feels unfinished and rushed most of the time. The best example of this is through the decision to have little to no music. While probably a deliberate choice in order to craft a symbolic silence, the quiet ends up becoming another failure for the film.

Cry Macho finds nothing in its silence and neither will you.