All Work, No Pay: A History of Women’s Invisible Labor

By Noelia Veras

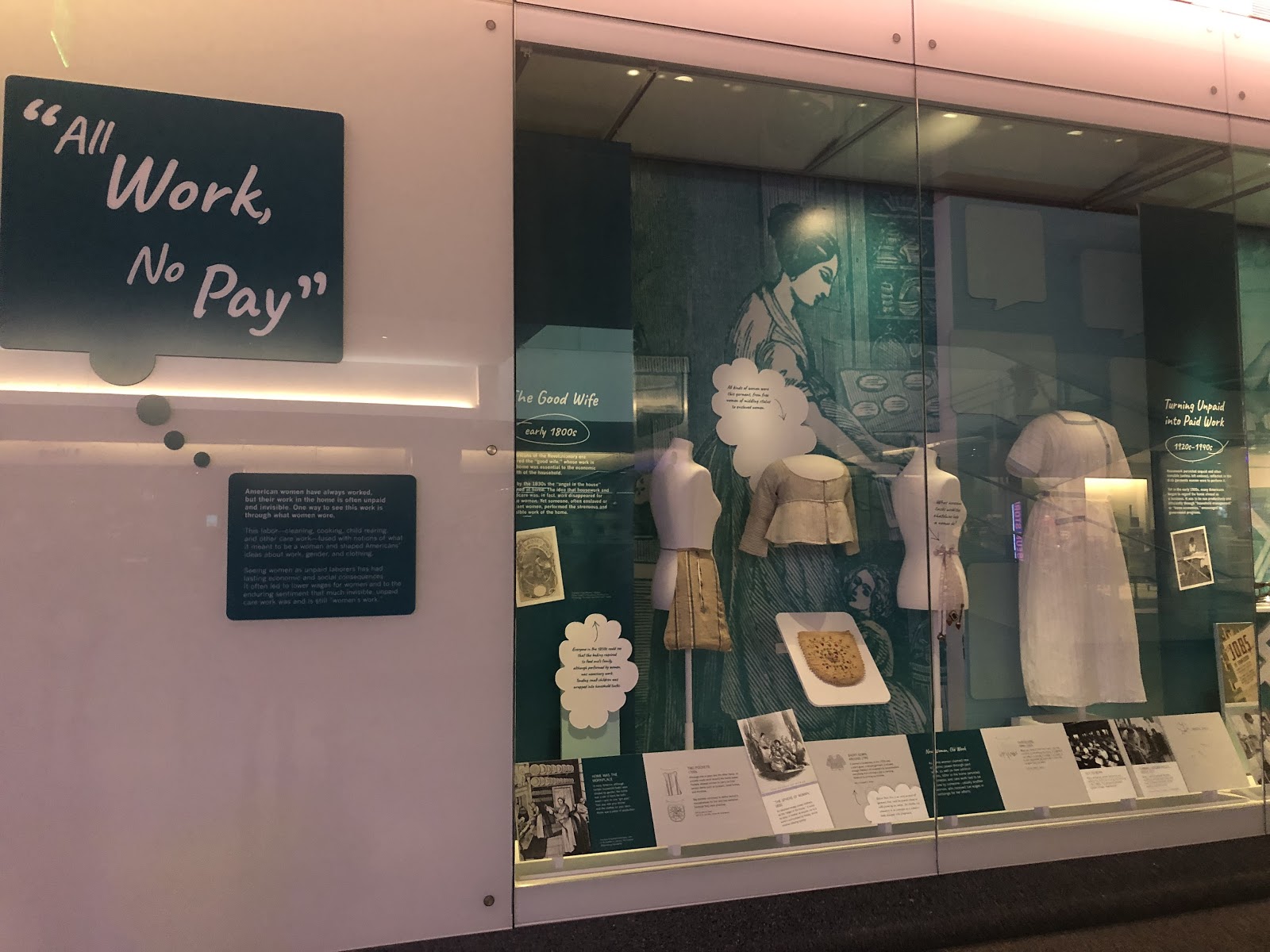

The National Museum of American History sheds light on the hidden labor of women throughout history in its new exhibit All Work, No Pay.

This exhibit is one of the first things that you can see when you walk in on the Constitution Avenue entrance. All Work, No Pay is ironically underwhelming, being displayed on a wall next to the gift shop. The exhibit illustrates the work of women through the garments that they wore in different time periods.

The exhibit begins with the early 1700s, highlighting the utility and convenience of women’s house dresses, especially those with multiple large pockets. The exhibit continues to the early 1800s and presents the clothing of the “good wife,” which took place during the Revolutionary era. The work of women during this specific period in time was crucial for economic success at home, as well as the general health of the people in the home. The apron represents the typical housework of a woman from the early 1800s.

The exhibit also delves into the era when women began to participate in the paid workforce. The workforce was no less misogynistic than society and perpetuated the concept of women doing meaningless chores. In fact, in the workforce, women still had to do the men’s laundry. The exhibit emphasizes that women even had to clean the offices they worked at.

Regardless of the new liberty afforded by paid labor in the late 1800s and early 1900s, women were still confined by the expectation to tend to the home. Women then used the Chatelaine to carry household tools which aided them while tending to the house.

Interestingly enough though, at this time, women also began to wear a shirtwaist to work symbolizing the image of the “New Woman.” In the 1910s, African American women were still a symbol of low wage labor and were especially mistreated, still having to participate in domestic labor.

In 1946 there was a rise in household work because of the rise of electricity and the arrival of new house cleaning machines. This raised the standard for women to do even more work, especially because of the introduction of the iron. The time that electrical tools saved was filled up with extra work for women anyway.

In the 1970s, an increasing amount of women began to demand monetary compensation for their housework. The exhibit presents several buttons and pins from the 1970s which advocate for the compensation of women for their housework.

The exhibit ends with the display of a stay at home mom’s clothing from 2018. The garment displayed is a pair of flare yoga pants. The heading of the display says “Yoga pants the New Housedress, 2018,” and the caption explains that women in the modern era still wear comfortable clothes to clean the house, and their work still goes unseen for the most part. Although the era of the housedress is over, the era of women’s hard work has never truly ended.