30 Years Later, Donkey Kong Country Remains Humanity’s Greatest Achievement

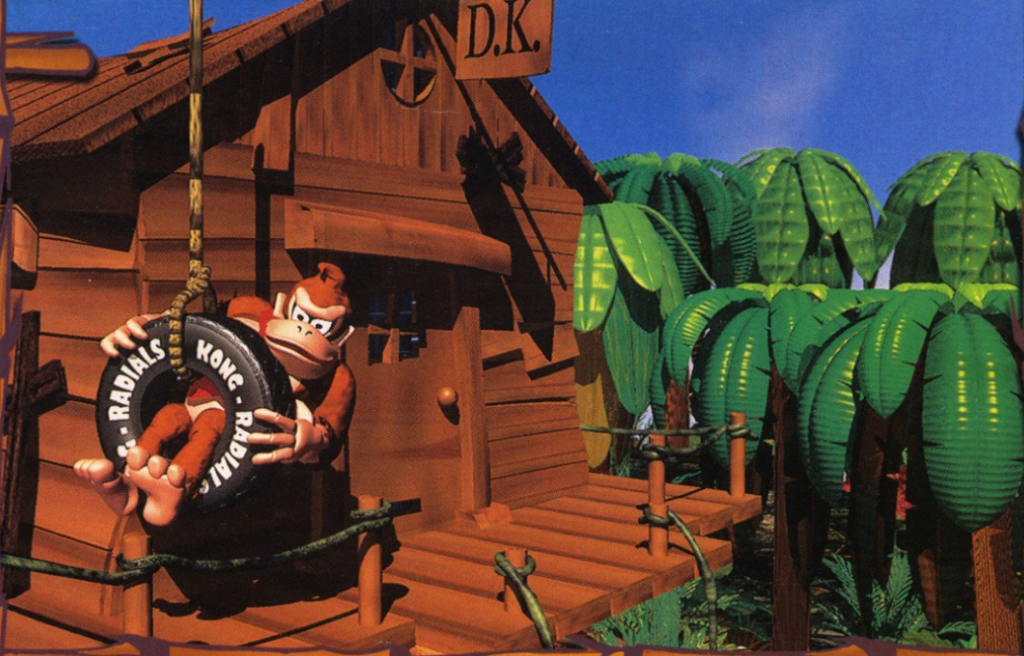

Image Courtesy of Nintendo/Rare Ltd.

By Joey Broom

Many consequential things happened in 1994: Nelson Mandela was elected president of South Africa, NAFTA came into effect, Israel and Jordan signed a peace treaty, and the World Wide Web became readily accessible to the average consumer. All of this, of course, pales in comparison to the events of November 18: Nintendo released Donkey Kong Country, the crowning achievement of human ingenuity.

While Donkey Kong Country received widespread acclaim and broke sales records when it was released, its reputation has fluctuated somewhat over the years. During the 2000s, it was frequently condemned as the epitome of style over substance to the point that a popular story spread suggesting that Shigeru Miyamoto, Donkey Kong’s creator, stated such himself in an interview. That story was proven false in 2019, and nowadays, most aren’t afraid to call the game what it is – a bona fide classic.

Despite its meteoric initial success in the arcades, Nintendo’s Donkey Kong franchise had faded into obscurity following the critical and commercial failure of 1983’s Donkey Kong 3. Mario had long usurped its position as Nintendo’s premier franchise, but by 1994, Nintendo was knee-deep in their console war with Sega and desperately needed a new hit to keep up.

Nintendo handed the Donkey Kong license to a small British studio, Rare Ltd. What made Rare attractive to Nintendo was their possession of Silicon Graphics workstations, the same kind used to produce the CGI in films such as Jurassic Park and Toy Story. And so came Donkey Kong Country, a game in which every character, object, and environment is a pre-rendered 3D model.

At the time, players were accustomed to games looking simple and cartoony, so imagine how shocking it would have felt to see a game that looked complex and believable. Donkey Kong Country looks like a playable stop-motion animation, akin to a Rankin-Bass or Aardman production. Characters move with a level of grace and fluidity you simply don’t see in other games of the time.

The world of Donkey Kong Country bears little resemblance to that of the arcade games. Instead of a construction site, the game takes place on Donkey Kong’s own island, a lush tropical paradise. The onesie-clad Donkey Kong Jr. is nowhere to be seen–he’s been replaced by the nimble and athletic Diddy Kong. (Who is also, in my opinion, a far better character.)

Donkey Kong had generally been known as a villain, but Country casts him as the hero, embarking on a journey to recover his hoard of bananas from the Kremlings, a band of crocodilian pirates led by King K. Rool. The supporting characters, from the wisecracking Cranky Kong to the animal assistants like Rambi and Squawks, make the world seem lived in, and it feels all the richer.

Donkey Kong Country plays nothing like the original arcade games, which simply challenged you to reach the top of the stage. It’s much more like Super Mario and Sonic the Hedgehog, requiring players to move from left to right as they avoid obstacles, stomp on enemies, and collect items. What distinguishes Country is how uncannily real it feels. The pre-rendered visuals aren’t just a gimmick; they define everything. Donkey Kong Island is a land of dense jungles, dimly-lit mines, blizzard-stricken mountains, and rickety railways. The ground is uneven, while platforms are integrated and contextualized within the environment.

For a cartoony platformer, Donkey Kong Country is surprisingly melancholic. A big part of this is the environments. The majority of its contemporaries were set in worlds that were bright, flashy, and fantastical, filled with blocky terrain and floating platforms, whereas Country’s are tangible, coupled with atmospheric lighting and weather effects that give many stages a grim, even oppressive vibe. This makes the journey feel even more perilous.

Equally important to establishing the tone is the soundtrack, courtesy of David Wise and Eveline Novakovic. It’s by far Donkey Kong Country’s greatest asset and remains one of the video game medium’s most celebrated scores, praised by the likes of Childish Gambino and the Nine Inch Nails. Wise and Novakovic blend bouncy jazz, environmental noises, and ambient music that’s either soothing or unsettling across tunes that set the mood for each environment perfectly.

To this day, the Donkey Kong franchise owes much of its identity to what Rare established in Donkey Kong Country. Although Donkey Kong game releases have become pretty infrequent (it’s been over ten years since Donkey Kong Country: Tropical Freeze, the most recent original game, was released), the franchise remains a mainstay in Nintendo’s lineup. It’s even getting a theme park land at Universal Studios next month! Donkey Kong Country’s 30th anniversary is certainly a milestone worth remembering.