Is It Worth the Read? Heart of Darkness

Image courtesy of tinhouse.com

By Caroline Morris

“The horror! The horror!” That is how I felt the entire time I had to read Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (and not in a good way).

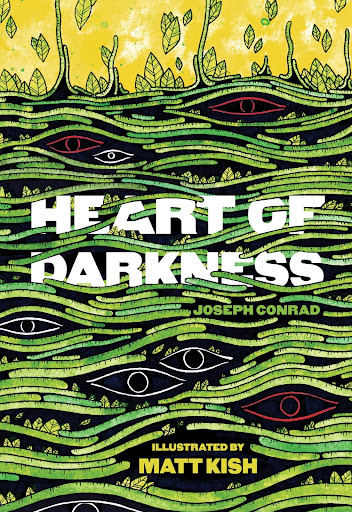

This classic novel follows the story of Charles Marlowe, who, in a frame narrative, recounts his excursion into the Congo through his employment with a Belgian company. Heart of Darkness was published in 1899 and is set in that same decade, so its original audience would have been aware of Belgium’s imperial hold over the Congo during this time: important context for this book.

Marlowe traverses through the African jungles via boat on the Congo River in an attempt to reach a high-level employee named Mr. Kurtz, who also works for “the Company.” The Company is meant to facilitate trade with and procure African goods (such as ivory) from the native Congolese, with an implicit sub-mission of civilizing the “savage” Africans, and Kurtz is one of its most successful leaders. Communication is shoddy, however, and rumors abound that Kurtz is dying or dead. Marlowe is sent to find him in what is ultimately a mentally unstable state, and Kurtz eventually dies.

Heart of Darkness is one of the most frustrating novels I have ever read and I would never wish reading it on another soul. I will acknowledge that great books are often difficult; I, for one, love to wrestle with Woolf and Dostoyevsky, but this novel is not one worth fighting through.

I was first assigned this book in my 11th grade “Brit Lit” class and I was the only one who read it. I wish I hadn’t. Though the novel is slender—most editions usually no more than 200 pages—reading it feels interminable. Every time I flipped the page and saw a dense block of text I wanted to tear the book in half. I do not blame my classmates for skipping this assignment. The only worthy parts of the text are small pull quotes. “The horror! The horror!” is a famous and impactful line, and the moment where a sailor pokes his head in and reports, “‘Mistah Kurtz—he dead,’” is hilarious in its perfunctory bluntness.

Aside from prose that is an unnecessarily laborious slog, I do not find anything in the book that gives it true “staying power” as a classic. The main argument I have heard about the value of Heart of Darkness is its statement about humanity and the corruptive nature of power.

To that argument, I say: “and?”

In that same high school English class, my teacher spent a good half of a class trying to get us to state the main message of the book. We, high-stress and high-achieving prep school girls, were tossing out nuanced and specific claims that our teacher shot down continuously. The attempts got more and more detailed and intellectual, but we were always wrong and she would not tell us the answer until the end of the class.

When the bell rang, she gave us that same answer about how power corrupts people and that that is the heart of darkness. We were irate. All of our answers had been arguments built off of that idea, but we never said it because of course that’s true. We perceived this “message” as an universally understood truth that did not need to be made explicit because it is so obvious.

This is still how I feel about the book today. The darkness conceit for the novel is not only a concept intrinsically understood from the teen years (at least), it is also not an innovative or unique theme to put into literature. It has been done before.

In Act II Scene I of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, Brutus decides that Caesar must die—not necessarily because he did anything wrong, but because he has undue power and that, historically, has proven to corrupt men. Brutus states:

“But when he once attains the upmost round./

He then unto the ladder turns his back,/

Looks in the clouds, scorning the base degrees/

By which he did ascend. So Caesar may./

Then, lest he may, prevent.”

This idea was present in a play 300 years earlier about an event that happened over a millennium beforehand. And we all know nobody does it better than Shakespeare.

The other argument for this novel that I have heard is its “representation” of the horror of imperialism, but I still cannot get behind this. First, even if this novel is meant to demonstrate the evil of white imperialism, it does not do it well enough. Using a white male narrator who is relatively neutral who goes in search of another white male who is an oppressor, but a mysterious, successful, somewhat beloved man, undermines any critique Conrad could be making. These characters are too intriguing and not purely evil so that a reader may have ambivalent feelings toward them and thus struggle to realize the greater critique at play. Additionally, the language used to describe the Congolese and women in the story feels unnecessarily derogatory (as such it has no place in this article), especially considering our author’s race and sex.

This book is not worth the excess of time it takes to read it. There is no saving grace to Heart of Darkness and it is ultimately upsetting to read with no greater purpose than to upset, which is a hallmark of a poor book.

Rather than simply not recommend Heart of Darkness, I will proffer another novel. If you want a book that engages with this time period and is a more dynamic and honest account of the racial and imperial issues at hand, read Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart. There you will get the representation Heart of Darkness claims to have without its failures.