Why Do We Like Sadness?

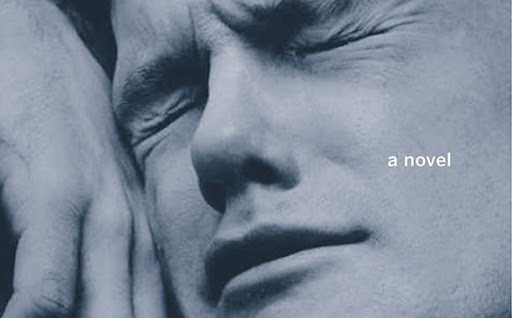

Image courtesy of Electric Lit

By Margaret Adams

A few months ago, there was a trend on TikTok to read a novel called A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara. It is a notoriously depressing but incredible novel that details the lives of four college friends, specifically the main character, Jude St. Francis. According to Book Trigger Warnings, the trigger warnings for this novel include violent ableism, child abandonment, eating disorders, abuse of every kind, suicide, racism, drug addiction, and many more.

The whole lure of the experience of this book was that it was so upsetting and sad; hundreds of people were putting themselves through extremely triggering descriptions and depressing stories. To the naked eye, it seems so odd that society would enjoy and celebrate this kind of content; why do people put themselves through so many painful experiences? Why do we enjoy media that’s so sad?

Media that is sadder or more negative in nature is often considered more genuine and more appropriate for higher-caliber examination; they are deemed more respectable and considered “real art,” unlike art or media that is happier in nature.

For example, romantic comedies are generally regarded as popcorn movies or “chick flicks,” and are never considered in the same caliber as dramas. Movies like 10 Things I Hate About You, Easy A, Mean Girls, and Clueless are only given the label “iconic” if it precedes romantic comedy; they are only regarded as classics within their own genre, despite being incredible films.

Removing the issue from the problem of apparent sexism, all of these movies and most romantic comedies have a happy ending. Whether it be because the story where “the boy gets the girl” isn’t realistic enough or because there are more pessimists than optimists in the world, the dramas with heartbreaking endings are the ones that win the Oscars. This all leads me to my own hot take: I think there is much more artistic merit to 10 Things I Hate About You than The Godfather (1972’s Best Picture Winner).

Another event that illustrates my point is when the musical artist Lorde released her latest album, Solar Power. Many people were disappointed in the album, specifically in that it was not as sad or melancholic as her last albums (anyone who has listened to “Ribs” off her album Pure Heroine knows exactly what I mean). The album ended up getting a 6.8 from Pitchfork, which is her lowest score on the popular music review site.

Catholic U psychology professor Dr. Becky Munoz says that negativity bias might have something to do with humanity’s love of the tragic and sorrowful, especially in the media.

“Negativity bias is a cognitive bias, so that means when we are processing information, we’re more likely to pay attention to, more likely to think deeply about, and more likely to remember information that has a negative connotation,” Munoz said. “So if it’s sad, or if it’s making us afraid, or if it’s making us angry, if it’s tied to those negative emotions, it’s more likely to be attended to, more likely to be encoded, more likely to be later recalled. So that means that even though we do pay attention to and we do remember and we process positive information, negative information just has an advantage.”

Negativity bias predicts that we are more likely to, at the very least, remember the information that evokes sadness, fear, and anger; this is why the sad dramas get the Oscars, why people love true crime podcasts, why Lorde’s last album flopped, and why A Little Life received 2015’s National Book Award for fiction.

“Any form of information that is given out on a mass scale has implications on a societal scale, not just an individual scale, so it’s not even just a matter of me as an individual being influenced more by negative information,” Munoz said. “It means that as a group or as a community or even as a culture or a society, we might be influenced to feel a certain way, think a certain way, or behave a certain way. Take negativity bias on an individual scale and just multiply it on a larger scale and you can see the implications it has for policy that we make, for interactions that we have with different groups.”

Our tendency to remember negative information is illustrated in our popular films, television, music, novels, etc; we have built an entire culture around our fascination with the sad and the scary. So, I want you to ask yourself: “What would society be like if we allowed positivity to rule the media we consume?”