Black History Is Missing In U.S. History Education

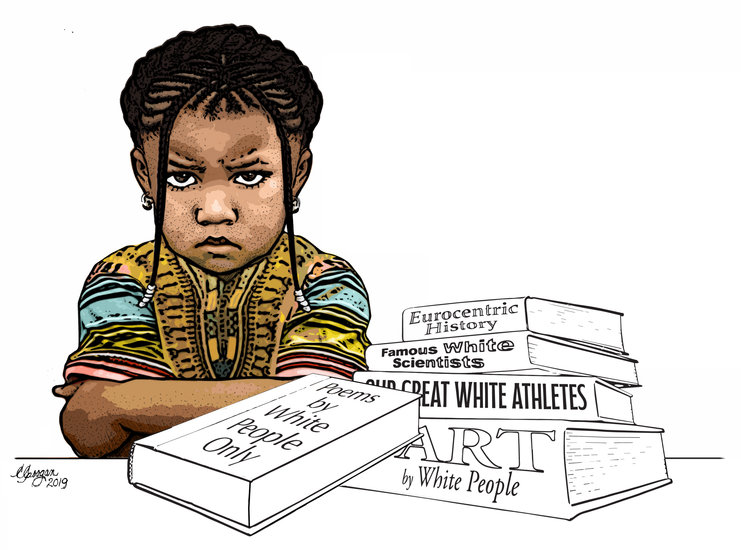

Image Courtesy of The Altamount Enterprise Opinion

By Lauren Seliga

You’re sitting in 9th-grade history class learning about the American Civil Rights Movement again. The sixth, seventh, and eighth-grade history classes covered the movement too. When is the American Revolution going to be taught? When will you learn about all of the achievements of white figures like John D. Rockefeller, Susan B. Anthony, or Thomas Edison? When will teachers stop using you as the example of a white colonizer just because you are the only white student in class? You take these concerns to the school administration and call for the expansion of white history in the school curriculum. The administration refuses to grant your request since the school spends a whole month—White History Month—teaching students about prominent white figures like Thomas Jefferson and Christopher Columbus, and don’t forget about the entire day in February dedicated to George Washington. The administration says that white history isn’t really that important to American history anyway so just be grateful the school takes the time to spend a month teaching about it.

This is a reality white students will never have to face, but unfortunately it is an experience all too familiar to Black students. If white history was treated like Black history, the education curriculum would have been developed immediately to include a more extensive teaching of white history and achievement. Black history is American history but in schools, it gets reduced to simply celebrating Martin Luther King Jr. Day and Black History Month. There is no shortage of prominent white historical figures who are common household names, but how many Black historical figures can you name besides Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, Frederick Douglass, and Harriet Tubman? The white narrative so entirely dominates our view of history that exclusively learning about white figures does not even seem out of place to us.

The Southern Poverty Law Center conducted a survey in 2017 with more than 1,700 U.S. social studies teachers and 1,000 U.S. high school seniors, and analyzed 15 state standards and 10 U.S. history textbooks. The goal was to understand how Black history is being taught in the United States and what American students are actually learning. The survey revealed:

- Only 8% of high school seniors surveyed could identify slavery as the central cause of the Civil War.

- Fewer than half (44%) correctly answered that slavery was legal in all colonies during the American Revolution.

- More than half of the teachers (58%) reported that they were dissatisfied with their textbooks, and 39% reported that their state offered little or no support for teaching about slavery.

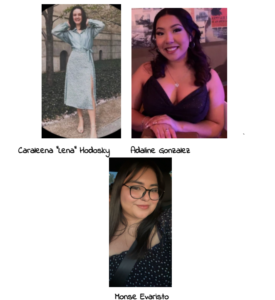

We conducted our own survey here at CUA with an average score of 9 out of 14, which according to the University’s grading scale, would receive a D (64.2%). The survey revealed:

- Over half (57.7%) were unable to identify how the Atlantic Slave Trade came about in the Western Hemisphere.

- Over half (73.6%) were unable to identify that the National Negro Improvement Movement ended because Marcus Garvey was arrested and deported to Jamaica.

- Over half (54.7%) were unable to identify Jean Toomer as a prominent author from the Harlem Renaissance.

- Almost half (49%) were unable to identify SNCC as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

Clearly, there is a need for better, more extensive teaching of Black history. In primary and secondary education, this starts with changing the state curriculum. If it is not compulsory—in other words, if it is not directly incorporated into the state curriculum—then many teachers will choose not to teach it. Black history is not given classroom time because it is not even in the state curriculum. For example, in Pennsylvania’s Academic Standards for History, for every 39 white historical Pennsylvanian figures, only four Black figures are mentioned; for every 18 white historical American figures, only five Black figures are mentioned. The Civil Rights Movement as a teaching standard is not even included in Pennsylvania’s Academic Standards for History.

At our own university, this starts with the creation of an Africana Studies program and an expansion of Black history courses. The University currently only offers two courses with a specific focus on the Black community and there are no academic programs that represent the history and culture of African civilization. CUA students Myciah Brown, Sophia Marsden, and countless others have been working tirelessly to change this. Their efforts have led to the creation of an Africana Studies Committee that will research, design, and pilot a course for the spring 2022 semester.

It is imperative that we move past the view that only teaching about Martin Luther King Jr. is enough to display the struggle, oppression, and achievements of Black Americans. In the absence of teaching Black history, the education curriculum is unbalanced and reinforces anti-black racism. Those who oppose the expansion of history curriculum to include more Black history may cite reasons for fear that it would promote the narrative that America is a wicked and racist country or that it is un-American propaganda. Former President Trump said an expansion of Black history in schools, as advocated by the 1619 project, would “dissolve the civic bonds that tie us together.” He calls for a restoration of patriotic education—an education that would leave out Black history. Opposition to an expanded Black history curriculum must stop being disguised as patriotism when it is really racism.

Right now there is an active bill in the New York State Senate that aims to amend the education law to expand New York’s education curriculum to include the history and achievements made by African Americans. If you are a citizen of New York, I encourage you to advocate for the passage of this legislation; if you are not a citizen of New York, I encourage you to advocate for similar legislation in your own state by following this legislative advocacy guide created by a few students enrolled in the POL312-The Civil Rights Movement course here at CUA. You can also expand your own knowledge of Black history by reviewing this education resource packet created by the same group.