On the Nature of Art: A Response

Image Courtesy of Artnet News

By Anna Harvey

As seen last week in Javi Mazariegos’ excellent piece, “On the Nature of Art,” we observe several key themes upon which I intend to draw: beauty, wonder, and ethics.

Indeed, it is essential for art to make itself noticeable to the viewer. Art is not and should not necessarily be vague; it must exist for a purpose.

I contend with the concept that all art is and must be beautiful; however, specifically in that what each individual finds to be beautiful will greatly vary. While there are some objective qualities to a universalized standard of beauty, beauty itself can be somewhat subjective, whereby some individuals find some aspects of art to be beautiful, while others find them to be ugly. As seen throughout human history, artistic periods and styles have shifted dramatically, from the lifelike beauty of the Renaissance to the melancholy and vague images of the impressionists, to the controversial method of mop painting, expanding upon the confines (or lack thereof) of modern art.

Similar to the growing genres of literature throughout the twentieth century, art has likewise evolved to incorporate the beautiful, as well as the ugly, not necessarily to uplift and console the viewer, but rather to encourage uncomfortable self-reflection within the viewer.

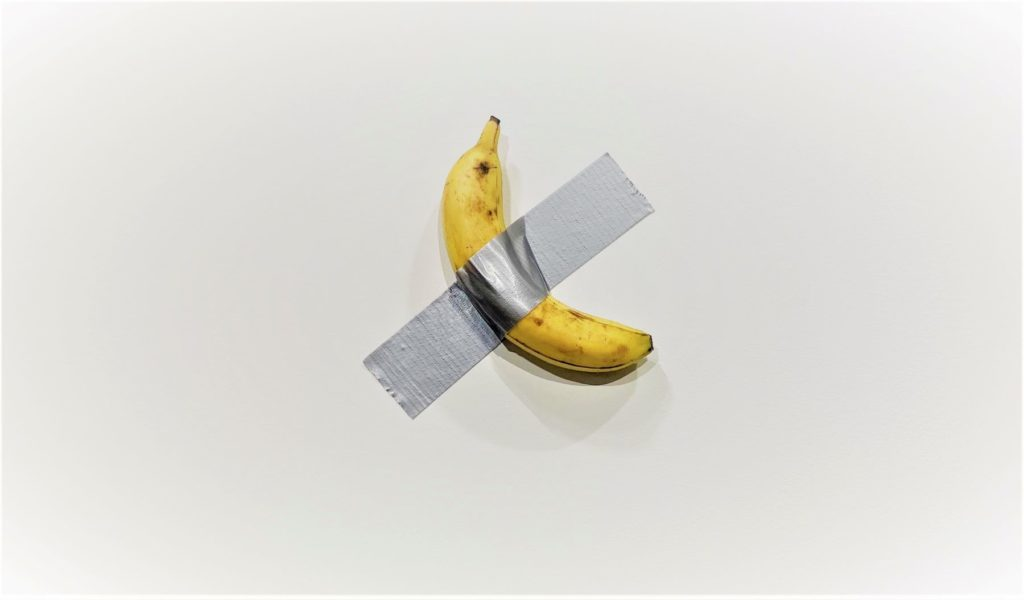

This does not mean that everything is art, however. Rather, an artist’s intention should be to promote some meaning that can be extrapolated (though imperfectly) by the viewer from the work itself. This meaning could differ from person to person, yet it must be contingent upon some variable that the artist provides, whether it be in a specific flourish, a specific or centralized object, or the very name of the work itself. For instance, a completely black canvas with no name would not necessarily constitute art. Additionally, the controversial banana taped to a wall also may not be art, as art generally implies a certain level of effort and involves the manipulation of materials to produce meaning; the effort it takes to tape a banana to a wall is minimal and laughable.

This leads to Mazariegos’ key point, which is that art ought to cause a sense of wonder in the reader. While this sense of wonder may not necessarily be prompted by objective beauty itself, it can be promoted by a certain feeling or memory evoked within the viewer when presented with an artistic piece.

For example, picture a cracked sidewalk, late on a rainy night in the city. Upon the ground lies a cluster of candy hearts, the kind you may see around Valentine’s Day, with engraved messages like “Be Mine” or “Miss You.” Some of the candies have begun to crumble, dissolving into the grainy, stained pavement. Greenish fluorescent lights from a nearby streetlamp cast an eerie greenish light upon the objects.

From this description, this scene appears to be the opposite of all objective beauty, as it evokes notions of decay, discomfort, or perhaps even disgust. Yet in a painting, as Mazariegos points out, this scene may empathize with us. The crumbling or decay of such romantic messages as found in the candy hearts can reach out to us where we are at a point in time. It may not necessarily soothe us, but it may confront us with an uncomfortable truth, one known only to us.

This proceeds to Mazariegos’ last point: that art must be ethical.

This is true to a certain extent; art should promote an inner dialogue that confronts our values and our ethics. Likewise, art should be used to promote good ethics. The way in which it presents these ethics, however, does not necessarily have to be in a positive or uplifting manner. Its counsel may not always be consoling and may instead violently confront us.

For instance, in Pablo Picasso’s famous work “Guernica,” he paints a disturbing scene of the bombing of Guernica in Spain. By all appearances, this work is not objectively beautiful; it can even be described as horrific. For viewers, however, this disturbing scene prompts a good examination of our own conceptions of human nature, war, destruction, and loss.

Ultimately, the true nature of art is found in the expression of the painter and likewise realized in the perspective of the viewer. In this sense, the nature of art is grounded in participation, a mysterious vision that may be comparable or may differ from the experiences of the individual. While it may be tempting to define art within certain abstracts, it is its elusiveness, the subjectivity of art that causes us to recognize our own potential, as well as the goodness and evil of our individual and collective humanity.

Like language, art’s inability to exactly convey perfect and ultimate truth may be well summed up in the words of Leo Tolstoy: “Art is the uniting of the subjective with the objective, of nature with reason, of the unconscious with the conscious, and therefore art is the highest means of knowledge.”