Majority Rules: Maine Lays Framework for Ranked Choice Voting at Presidential Level

Image Courtesy of Maine Beacon

By Justin Lamoureux

From an electoral standpoint, the state of Maine has always yielded somewhat of an “independent streak.” It is one of only two states (the other being Nebraska) that divides its electoral votes by congressional district; for several election cycles, it was also the only state in New England to hold a presidential caucus, in lieu of a primary. This characteristic was solidified last week, when the state’s supreme court cleared the way for ranked choice voting in this year’s presidential election.

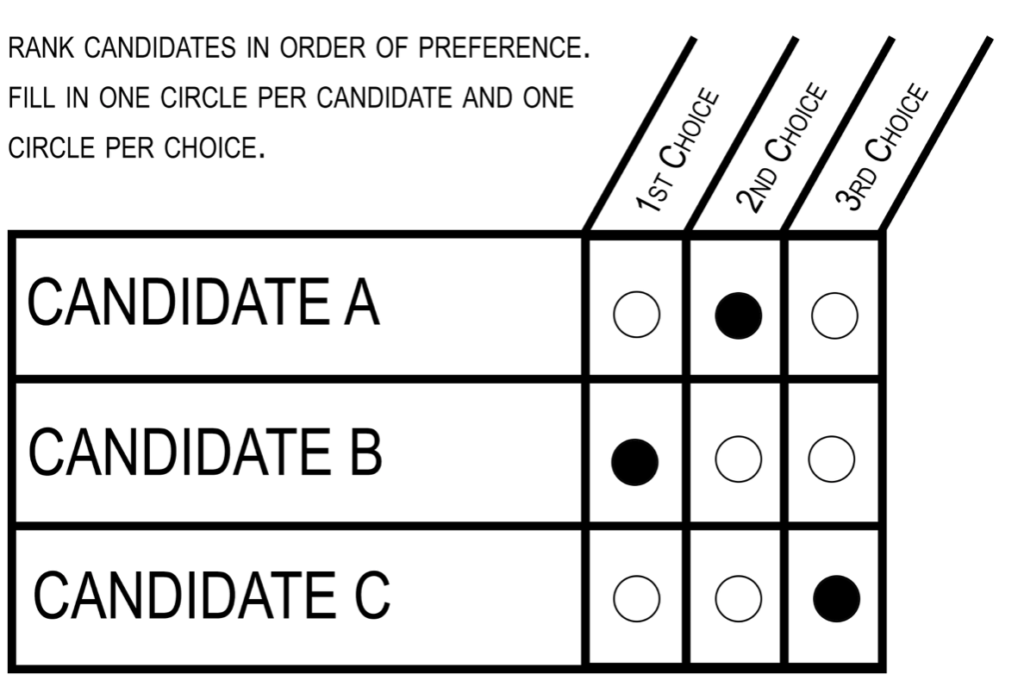

In practice, ranked choice voting is a relatively simple concept: it allows voters to select candidates in their order of preference. In other words, rather than voting for a single candidate, voters will state their first, second and third choice, respectively. A majority of states use ranked choice voting in some capacity, but only in primary and local elections. Maine will become the first state to employ this procedure in a federal election.

Here’s how it works: in order to win, a candidate must have a majority (i.e. at least 50 percent) of the vote, rather than a plurality (the most votes). In Maine, ranked choice voting will only be employed when three or more candidates are present on the ballot. Each round, the candidate with the least number of votes will be eliminated until only two candidates remain.

If there is no clear winner (i.e. a candidate with a majority of votes) on Election Night, the state of Maine will resort to ranked choice voting rounds. Officials there have developed a plan for this scenario: according to CNN, couriers will be sent around the state to either collect actual ballots or memory devices. These will be delivered to a secure location at the State Capitol in Augusta where they are further processed with a high speed tabulator. Kristen Muszynski, Communications Director for Maine’s Secretary of State, estimates that “the process takes about a week, a week and a half.”

Of course, voters are not required to rank their choices. They only need to vote for their first choice. However, if they choose the same candidate for their first and second choice, it counts as an “over vote” and your vote will not be counted.

The practice of ranked choice voting has received a mixed reaction. Proponents argue that, in a large field of candidates, it ensures that whoever wins the election has support from the majority of voters. Not to mention, this can also prevent “spoiler” (i.e., third party) candidates from gaining traction in a way that diverts election results in favor of a major party contender who might otherwise be favored to win comfortably.

Opponents, meanwhile, allege that such an approach is not rooted in democratic ideals and will only lead to increased electoral dysfunction. Gordon Weil, a former Maine state agency head and municipal selectman, has asserted that ranked choice voting will create a system in which “the result could be more like Family Feud than a decision about one of the most important choices people can make.” There is a possibility that ranked choice voting, as a policy, will be (extremely) short-lived; opponents in Maine have announced their intentions of delivering the case to the U.S. Supreme Court, quite possibly in the foreseeable future.

Looking ahead to November, there is a likelihood that ranked choice voting will have little impact on the outcome of the election. Granted, Maine’s second congressional district – located in the northern part of the state – is expected to be competitive at both the congressional and presidential levels. It is unlikely, however, that either candidate (in either race) will not receive 50 percent of the vote outright. What’s more, there has been no polling to suggest that any third party candidates have potential to gain noteworthy support.

Essentially, ranked choice voting is a contingency plan. The chances election officials in Maine will need to execute it are relatively slim. Nonetheless, it reflects two significant trends: A historical development in the world of presidential politics, and a precedent to actively avoid the “worst case scenario.”

Maine’s second congressional district only accounts for a single vote in the electoral college, and will unlikely have a monumental effect on the election. However, in the absolute closest presidential election, where the winner hinges entirely on one vote (again, unlikely, but experts foresee numerous scenarios in which this could occur), this generally insignificant constituency in New England could be the deciding factor. If the district, in turn, is extremely close – with neither candidate reaching the 50 percent threshold – ranked choice voting could make a remarkable difference.