How the Coronavirus Pandemic is Affecting Those in Immigration and Customs Enforcement Detention Facilities

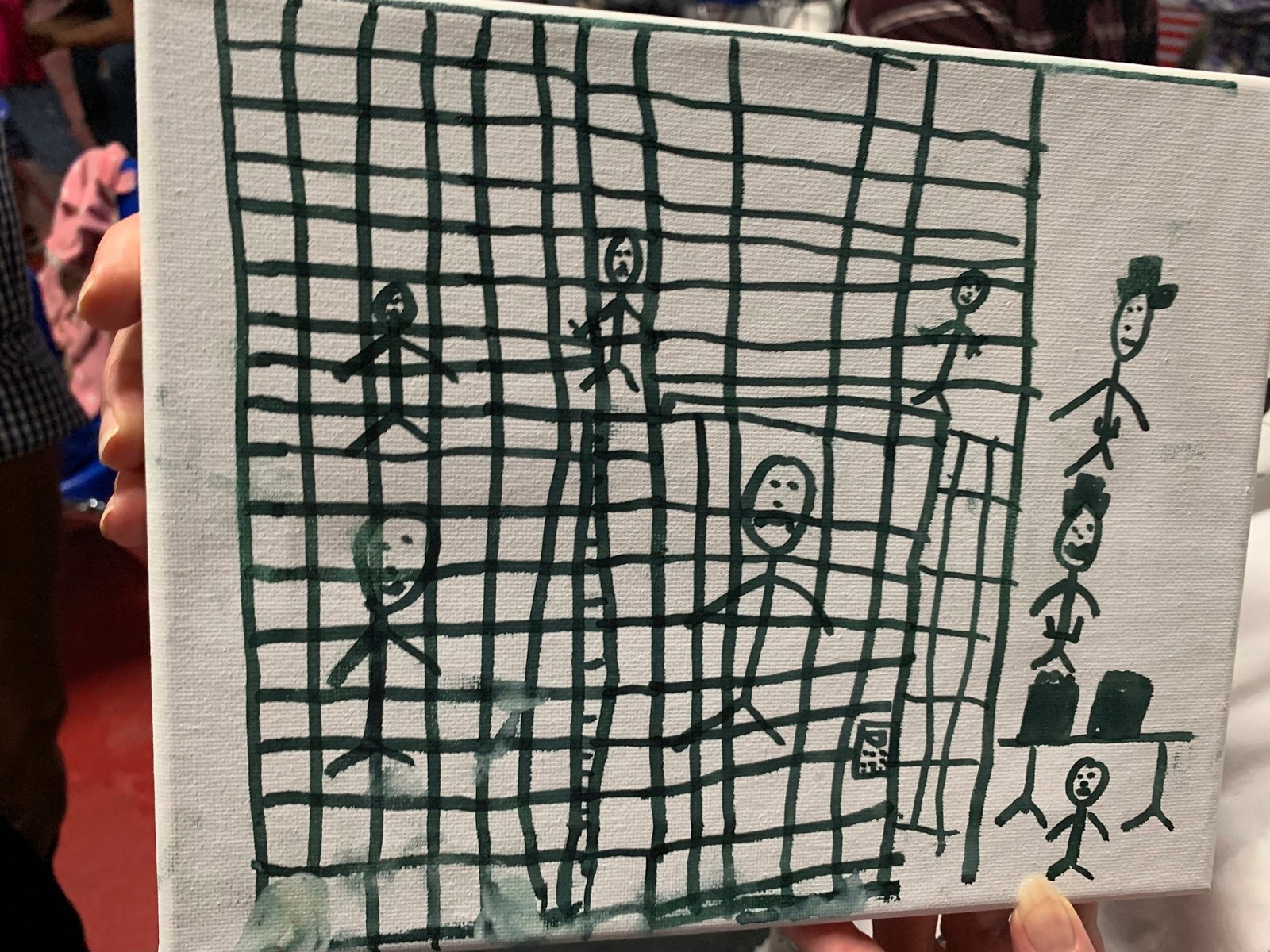

Illustration by child detainee in detention center; Photo Courtesy of the New York Times

By Jessica Fetrow

In recent weeks, the United States government, alongside several health organizations worldwide, has released multiple statements desperately urging individuals to maintain basic hygiene and practice social distancing in order to combat the COVID-19 pandemic. For those individuals detained in Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention facilities within the United States, the reported overcrowding and hygienic standards are proving to be a potential breeding ground for the novel coronavirus.

Currently, the United States maintains the largest immigration detention system in the world and is holding approximately 37,000 undocumented immigrants within various detention centers throughout the nation. Already a notorious political and social humanitarian crisis, the development and persistence of the respiratory disease has created a new topic of conversation for politicians and humanitarians alike: what measures are being taken to prevent coronavirus outbreaks in these detention facilities?

In a report released by Amnesty International on April 7, United States immigration detention centers “have failed to adequately provide soap and sanitizer or introduce social distancing.” These facilities also have not paused the “unnecessary transfers of people between facilities in the interest of public health, routinely transporting thousands in and out of facilities.” According to ICE, there has been an increase in the number of confirmed cases within the detainee population, jumping from nearly 90 confirmed COVID-19 cases nationally on April 17 to 287 confirmed cases as of April 23. The confirmed cases among ICE employees have also seen a slight increase, rising from 25 cases to 35 cases in the past week. There have been 88 confirmed cases in ICE employees not assigned to any detention facilities.

According to the official ICE website, preventative measures and new precautions have been put into place, as well as adhering to CDC regulations. The latest version of the ICE COVID-19 Pandemic Response Requirements guidelines updated on April 10 emphasizes the three objectives of the new implementations: preparedness, prevention, and management. Within these provisions, ICE staff members are required to “review sick leave policies” and “determine minimum levels of staff in all categories required for the facility to function safely.”

In addition to these staff requirements, facilities are required to “post signage throughout the facility reminding detained persons and staff to practice good hand hygiene and cough etiquette,” as well as perform COVID-19 pre-intake screening for all new entrants and suspension of in-person visitation. New entrants are also expected to quarantine 14 days before joining the rest of the population.

Even with these preventative and management measures by ICE in place, there have been concerns over the efficiency and capability of the enforcement of such procedures.

“I have visited detention facilities in Texas and Virginia where, in the best of times, the medical services and staffing are woefully inadequate to meet the physical and psychological needs of immigrants detained in the facility,” said Catholic University law professor and Director of the Immigrant and Refugee Advocacy Clinic of Columbus Community Legal Services Stacy Brustin. “Overall, the detention centers are also not set up to contain [the] contagion.”

Brustin described the extremely close quarters of the facilities she had visited in Texas and Virginia, organized either with rows of bunk beds or cells with four individuals per room. In response to such sleeping arrangements, ICE said they are advising head-to-toe sleeping arrangements among detainees when possible. Requests by detainees taking measures to avoid the virus in close quarters environments are frequently dismissed.

“One client reported sitting in the dining area when a man at his table began coughing profusely,” Brustin said. “He requested to move to another table, however the official monitoring the cafeteria refused his request.”

Several states, such as New Jersey, have begun removing a select number of detainees deemed as non-violent and non-flight risk, who have also been determined to be more susceptible to the virus due to previously reported chronic health conditions. Such individuals have been released with ankle monitors until they are expected to attend scheduled court dates. According to John Sandweg, former acting director of Immigration and Customs Enforcement, only a small percentage of those held in ICE detention facilities have been convicted of violent crimes. These measures were implemented after the deaths of three employees at the Hudson County Correctional Facility in New Jersey and ten confirmed cases within the ICE detainee population; nearly one-third of immigrant detainees at the facility have since been released according to NPR.

However, these measures are argued by many to be inadequate in protecting the health and safety of the humans contained in these facilities, with federal courts mandating certain releases after immigration attorneys filed habeas corpus lawsuits, alleging that it is unconstitutional to hold detainees in such environments during a pandemic.

“Detained immigrants are well aware of the pandemic spreading throughout the U.S. and they feel helpless to protect themselves from this looming threat,” Brustin said. “Pro bono and volunteer lawyers across the country are petitioning ICE to release detained immigrants on humanitarian grounds. While ICE is approving some of these petitions, many are denied.”

“We are about to witness the tragic consequences of those policy decisions if the federal government fails to release more immigrants from detention as soon as possible,” Brustin continued.

ICE continues to update its website and provisions based on CDC guidelines and states that it is closely monitoring the COVID-19 situation.