Shatter the Silence

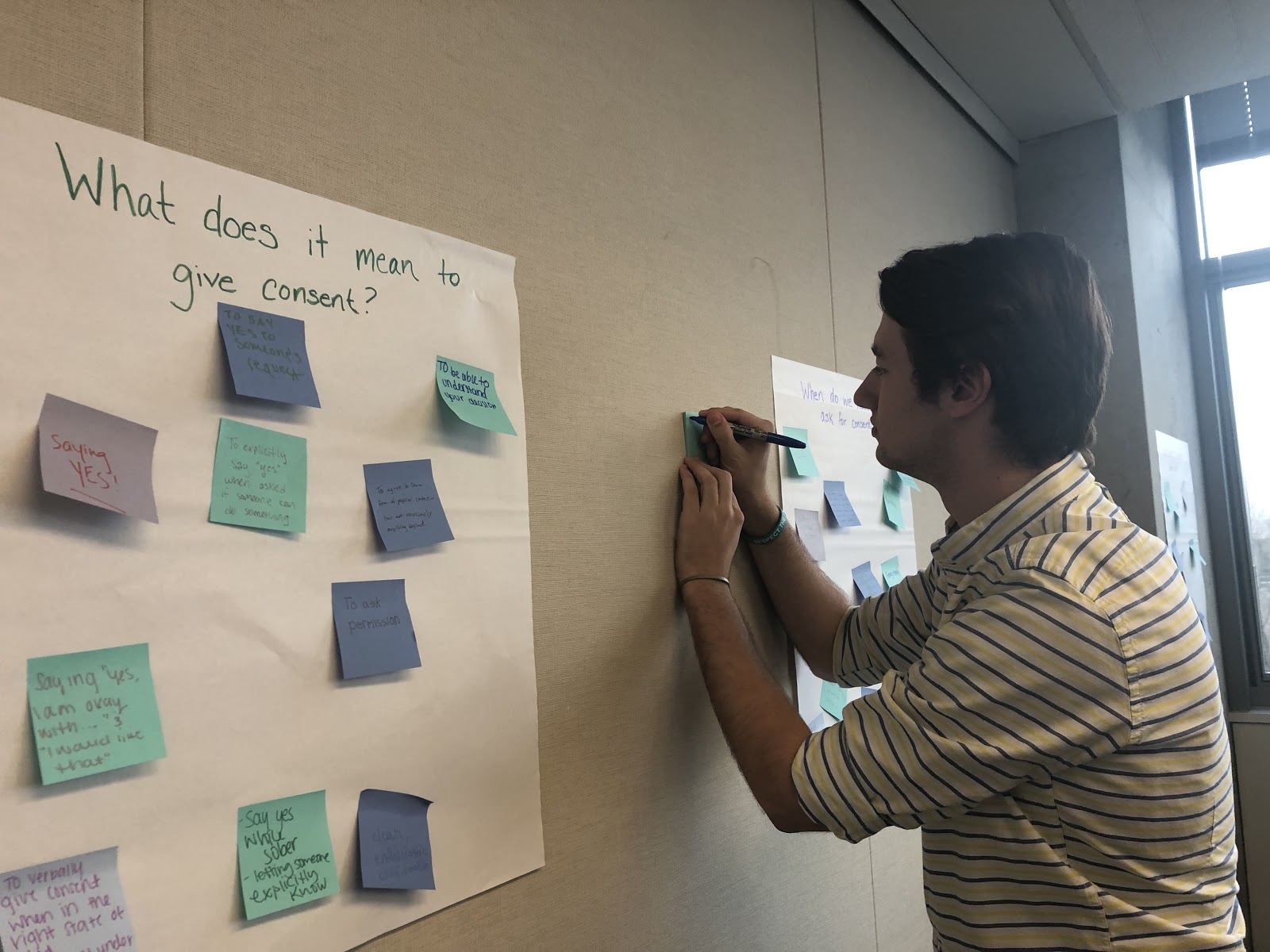

Pictured: Senior social work major Matt Finley. Courtesy of Noelia Veras

By Noelia Veras and Theresa Whitfield

Catholic University’s Counseling Center and PEERS (Peer Educators Empowering Respectful Students) joined together to lead a discussion about consent and sexual assault in an event called Shatter the Silence. This event covered the basics about consent and delved deeper into the intricacies and myths surrounding consent, because April is Sexual Assault Awareness Month.

The event was held on Tuesday, April 9 in Room 323 in the Pryzbyla Center. The event had a great turnout and an enthusiastic crowd. Additionally, this was a highly interactive group and the speakers, who are counselors from the counseling center on campus, encouraged everyone to participate in a couple of activities.

The first activity required everyone to get out of their seats and respond to some questions regarding consent on a large poster paper hung up on the back wall of the room. The questions were: “What does consent sound like?” “When do we need to ask for consent?” “What does it mean to give consent?” “What can we do or say if we do not give consent?” After everyone answered, the counselors opened up a discussion about the questions, talking about how consent means a firm yes and explaining that the absence of a no does not mean yes.

The counselors noted that consent is necessary in any intimate act whether it be physical or emotional. To give consent is to not leave any ambiguity and be completely clear when saying yes. When one party is saying no, the counselors recommended reaching out to others for help or adamantly saying no.

The second activity was called “The Consent Game” where various scenarios were present and attendees raised either a green heart for yes, a yellow heart for maybe, and a red heart for no. One of the scenarios questioned whether or not a senior in college and a freshman in college dating each other was consensual or permissible and many people said the yellow heart should be raised, because sometimes differences in experiences could be detrimental for the individuals, especially the freshman. Power dynamics can also create an unhealthy relationship.

The scenarios ultimately lead to the same place: consent is not simple, and the conversation should be nuanced, because sometimes people find themselves under the influence of drugs or alcohol saying yes and not meaning what they say.

The counselors then played a video that conveyed the definition of consent in simplified terms. Instead of talking about it in the traditional sense of being physically intimate with another person, the individual in the video was asking for consent to use someone else’s phone. In one scenario, the woman tried to take the phone by force and in another, she pressured the individual to give up his phone because a mutual friend gave up hers. In these scenarios and multiple others, the person believed consent was given, but really, this was not the case. While the video may have oversimplified the heavy topic, it did provide clear boundaries to which everyone watching could agree.

“Having events like this, in an interpersonal setting, is really important because its not something people can talk about lightly since it connects to vulnerability and values,” said Emily Macaluso, a sophomore psychology major who planned the event. “I just think its really important to be able to be open but put your thoughts out there anonymously and have other people talk, because it encourages you to be honest.”

Overall, this event opened up a dialogue that often goes unexplored, but is vital on a college campus. Consent is something that can easily be overlooked, especially in the small, seemingly insignificant moments. Creating a dialogue and educating people on its absolute necessity in all scenarios are some of the most important steps towards changing the culture of consent