Is the Homage Bad for Art?

Courtesy of The Paris Review

By Eduardo Castillon

This is an independently submitted op-ed for our Quill section. Views and statements made in this article do not necessarily reflect the opinions of The Tower.

“The more virgin our eyes are, the more we have to say. The most detestable habit in all modern cinema is the homage. I don’t want to see another goddamn homage in anybody’s movie” famous director Orson Welles spoke to a Paris film school in 1982. Widely regarded as one of the most foundational directors of all time, Welles warned prospective directors about being “marinated” in too many movies while still emphasizing the importance of watching “great films”.

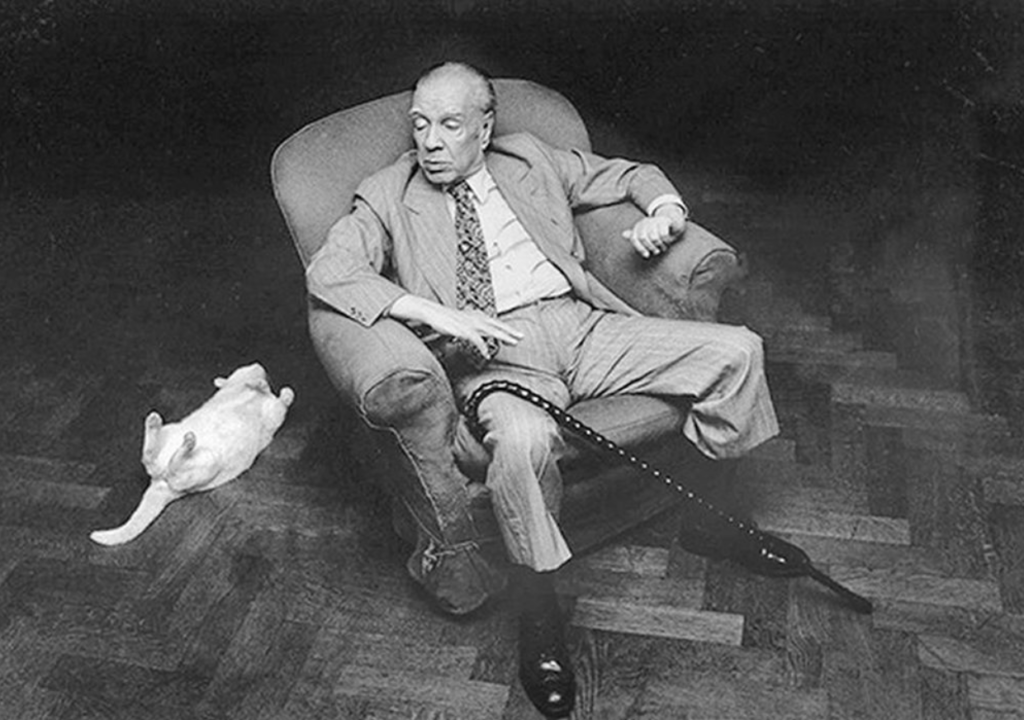

Welles’ strong opposition to the homage however contrasts starkly with cinephile director Quentin Tarantino’s style of imitating some of his favorite movies in his work. Welles longs for the artist who has something original to produce to his industry, while Tarantino would seem to hold the homage as respecting the past, even if he himself considers it “stealing”. Both views of art seem opposed to one another, one modern, the other postmodern. How to resolve this? I believe our answer lies in a certain Argentinian author, Jorge Luis Borges.

After suffering a traumatic brain injury and contracting blood poisoning, Borges attempted to test his faculties by writing. Scared he had lost all of his prior ability, Borges chose not to write poems or articles, of which he’d written hundreds, rather he wanted to write something he’d never done before: short stories. What was produced was a fascinating work of meta-fiction, Pierre Menard, Author of Don Quixote.

The story is written from the perspective of a literary critic praising the unfinished work of fictional author Pierre Menard, Don Quixote. You may know the original Don Quixote was written by Miguel De Cervantes, however, Menard’s work is neither a copy nor a re-translation, it is Don Quixote’s word-for-word “recreation” that reflects Menard’s life and perspective.

Menard first attempted to become the kind of person who’d spontaneously write the same book. He imitated Cervantes by learning 17th-century Spanish, adopting Roman Catholicism, and waging war with Turkey. Needless to say, he found this approach too easy. Instead, Menard wanted to see how Don Quixote changes if rather than a 17th-century Spaniard, its author was a 20th-century Frenchman. Even though the words are the same, the literary critic is astounded by Menard’s writing.

The meaning of Menard’s Don Quixote has changed because of the reader’s impression of the author. Borges’ exploration of texts and the cultural contexts they are written in presents a new form of reading, one that produces an entirely different work depending on the background and meaning an author brings to their work.

Borges’ short story is not simply to be understood as a case of the “death of the author”, but rather that the context and time surrounding a text dictates our reading of it to such a degree that reading itself becomes a fundamentally creative action.

Borges ties the authority of a text to both the reader and the author in a stunning union of modernist and postmodernist writing. While this may be a great deal to process, the implications of Borges’ work on our initial conflict between directors now can be clarified.

Tarantino’s style of directorship is his own despite the original films he’s stealing from. Audiences approach his films as Tarantino films, they experience them totally detached from their sources of influence. Welles likewise is understood to be the great director behind Citizen Kane, and that context further transforms the act of viewing Welles’ films. Our “virgin eyes” are not so pure, but interwoven within a web of contexts.

The director and audience are participating in a totally original act framed in the context of the films being viewed. The homage is really inconsequential to the meaning or creativity of a work when compared to the relationship between the artist, viewer, and the piece of art itself. The details of that relationship such as the background of the author, the approach of the viewer, and the task of the artwork itself, all enable us to create inspired and truly original works of art.